By

![]()

Virtual Pulp consistently reviews hidden gems in the cyber-slush pile of online book shopping. Independent authors who you might have never heard of otherwise get their books in the spotlight. The Infamous Gio occasionally gives them a microphone, too, when he conducts interviews. Recently Gio got independent author Shattuck O’Keefe to give an in-depth interview, and is sharing it with you today.

Q1: The Spirit Phone is your first published full-length novel. Why this book and why now?

O’Keefe: As for why this book: The idea for it hit me suddenly one day in August 2009, and I couldn’t let go of it.

As for why now: It really should have been much earlier, but from the time I conceived of it, various life events got in the way of getting it written. I finally got a complete draft done in early 2019, then managed to land a publishing agreement with BHC Press in late 2020, with the release in November 2022. (The audiobook, which came out the following June, earned Daniel Penz, the narrator, a 2023 Voice Arts Award.)

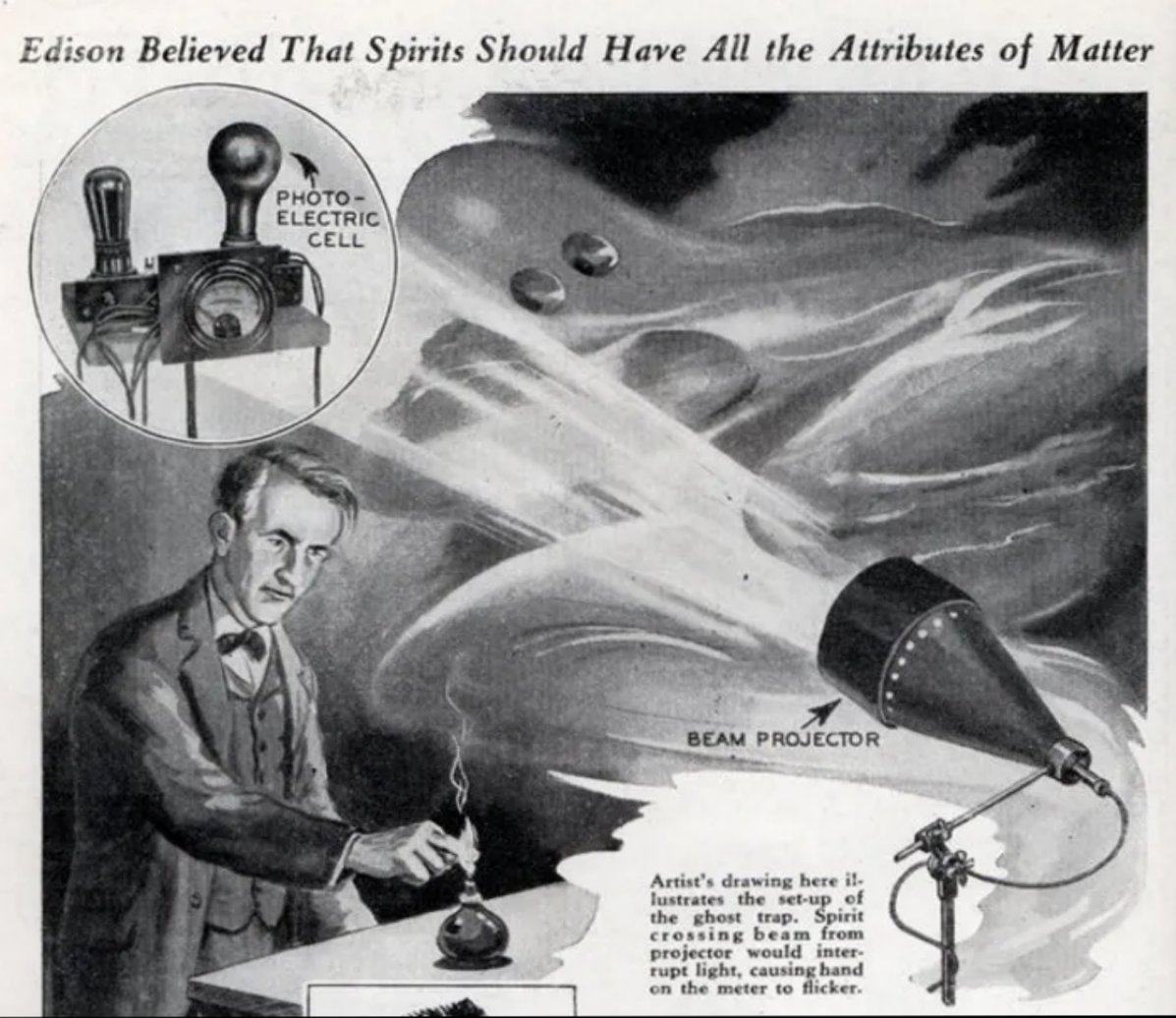

I’ve always loved books, and I decided to write a novel. I’ve long enjoyed speculative fiction as well as allegedly true tales of the supernatural. (Even if you take the latter with a grain of salt, they make for interesting reading.) I’d been mulling over ideas for several years, and one day I was re-reading my copy of Phantom Encounters, a volume of the popular Time-Life book series called Mysteries of the Unknown. It contains a chapter on the alleged “spirit phone,” a device to attempt communication with the dead which Thomas Edison claimed in interviews that he had been trying to develop. Suddenly the idea hit me: What if Edison had actually built such a device, and what if it worked? That could be the premise of a novel, I thought. So, I wrote it.

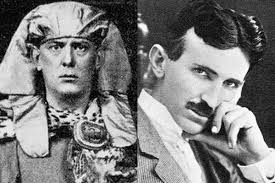

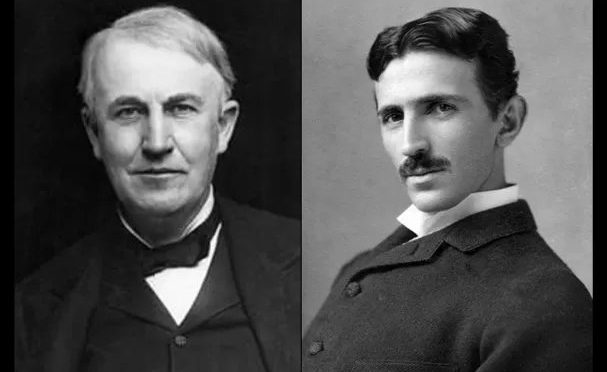

Edison is a key supporting character, while the protagonists are occultist Aleister Crowley and inventor Nikola Tesla, who investigate the secrets of the spirit phone as its users increasingly fall prey to insanity and suicide.

In the course of my research for the book, I learned about a claim circulating online that Edison stole the spirit phone idea from Tesla. There is no evidence for this whatsoever. I wrote about it in an article posted on Medium.

There’s also a short story connected to The Spirit Phone, titled “A Spirited Conversation,” which appeared in the literary magazine The Stray Branch (Fall/Winter 2021). The magazine is in print form only, but the full text can be read on my website. It previously appeared in Suspense Magazine (Summer 2020), though it’s a slightly different version than the 2021 publication, which I consider definitive. There is a beautifully done audio recording of “A Spirited Conversation” by The Spirit Phone audiobook narrator Daniel Penz. It’s a little over 16 minutes long.

Q2: the way I found your book was purely coincidental. I was looking for new content to cover and (as I often do) I was reading some of the Amazon reviews on The Spirit Phone, when this specific reviewer caught my attention by negatively highlighting the lack of female characters in your book. I knew immediately I had to get you on VP!

What do you think of this modern trend that requires or even demands at times that authors meet a particular demographic representation quota in their stories?

O’Keefe: I don’t agree that a novel or short story must reflect a demographic checklist to be a “proper” work of fiction. Though if, as a reader, the lack of some category of human or other is a deal-breaker for you, so be it. There’s no such thing as a novel that will appeal to everyone.

Your question reminds me of one review (really a non-review) of The Spirit Phone which listed the book as a DNF simply because the reviewer couldn’t get interested in characters who were white men. Nothing whatsoever is mentioned about plot, premise, editing, dialogue, world-building, or anything else that makes a novel a novel. I can’t consider that to be a book review. If you label a novel unreadable simply because you find the skin color or sex of the characters objectionable, you have not evaluated the novel. That, in a nutshell, is the problem with trying to assign “diversity” requirements to a book. Still, I find this to be the exception rather than the rule in the reviews I’ve read.

Besides, diversity of characters is not just things like race, sex, and sexual orientation. There are the characters’ motives, objectives, personal values, temperaments, skills, etc. The protagonists of The Spirit Phone are historical figures. Aleister Crowley was a hedonistic, smart-aleck, pipe-smoking, drug-using adventurer who delved into the occult. He set mountaineering altitude records in an era before bottled oxygen and high-tech winter clothing. Nikola Tesla was a straightlaced, germophobic, non-smoking, work-obsessed genius who made invaluable contributions to electrical invention. Their personalities were very different, and that’s the kind of diversity I tried to depict in my novel. If you want the more “standard” usage of diversity, Crowley’s bisexuality and Tesla’s apparent celibacy are alluded to, but these aspects are included because that’s part of who they were, not for the purpose of satisfying a perceived diversity checklist. Horror author Terence Taylor expressed a view similar to my own on this point in his review of The Spirit Phone for Nightmare Magazine.

As for the particular review you mention, by horror author and editor Amanda Lyons, I see it as a mixed review rather than a panning of the book. There is also praise, and I actually thanked her for it. However, I disagree with the portion quoted below, which I think partly exemplifies the issue you mention:

“For my own tastes this was a bit dry and impersonal and I was chagrined to find very few female characters (and that those who were there came in the form of uncouth harpies and demons at the beck and call of male sorcerers).”

It’s unclear what “personal” elements are seen as missing, so I’ll skip that. As for the rest: Female supporting characters include Sadie the bookseller, who is indispensable in helping Crowley and Tesla. There are two female demons: Lirion and Elerion. Yes, they are bound to male mages (Crowley and antagonist Ambrose Temple, respectively), but Lirion voluntarily goes beyond the scope of her obligations to help Crowley and Tesla, while Elerion–also in freely choosing to aid the protagonists–gives Temple the ultimate dressing down as she declares herself absolved of serving him. This is after she telekinetically snaps the neck of a monster that tries to sexually harass her. Thus, the female demons are much more than simply things to be used by the male mages. There is also Martha, a woman who is crucial in highlighting the moral bankruptcy of Temple and his plan. The only female characters who could reasonably meet the “shrill harpies” description are two in total: one female spirit contacted through the spirit phone and a young woman who Crowley and Tesla encounter in New Jersey. So, with all due respect to Ms. Lyons as a far more prolific author of fiction than myself, I can’t agree with her on this point.

When I read that review, I was reminded of an academic paper I’d written on the female characters of Ernest Hemingway’s unfinished story (possibly intended as a novel) “The Last Good Country.” In it, I quote a paper by literature professor Margaret Bauer, who states:

“Hemingway is often criticized for his one-dimensional characterization of the women in his fiction. I would suggest that such critics are actually arguing with Hemingway’s choice of focus. The problem they have with Hemingway’s female characters is not that they are one-dimensional (the numerous studies of them suggest otherwise), but that they are usually not central characters. I would argue that it is the writer’s prerogative as to whose story he or she is most interested in telling.”

I agree with Professor Bauer, and I think her reasoning applies to either a literary giant like Hemingway or an obscure “genre fiction” debut novelist such as myself. Besides, there is no shortage of books with female protagonists in various genres, including fantasy, science fiction, and horror, if that’s what you’re looking for.

Anyway, mixed reviews or bad reviews are a fact of life. Even the Harry Potter books were roundly condemned by Harold Bloom, perhaps the most famous and influential of American literary critics.

Q3: speaking of modern, what I loved about The Spirit Phone is the respect you showed for the period of time/locations where the story takes place. New York, her streets, restaurants, hotels, daily papers, everything is so detailed and so faithful to that time. Do you feel it’s important to keep that level of historical faithfulness even in alternate history fiction?

O’Keefe: Yes. With the caveat that I think of The Spirit Phone as a cross-genre novel, it is among other things an alternate history tale, and I think it’s important to strive for historical accuracy. If you’re going to depict the year 1899 without an effort to do so accurately, why bother calling it the year 1899? Unless, of course, you introduce anachronistic aspects–historical inaccuracies–as a deliberate decision in the service of the story.

One way to do this is to have the entire world be “openly” anachronistic, such as in William Gibson & Bruce Sterling’s novel The Difference Engine: The computer (a steam-powered variety) has become a reality in the 19th century, resulting in a global political order which includes a much more powerful British Empire, an independent Confederacy, and a Marxist republic on Manhattan Island. Another example of this approach is Bonsart Bokel’s Association of Ishtar series.

In The Spirit Phone, which is set in 1899, I tried to make the publicly known technology, infrastructure, political situation, etc. the same as our actual history (with the exception of the spirit phone itself, which is being marketed by Thomas Edison as a consumer product). If you suddenly appeared in the New York of the novel, it would look just like the real 1899 New York. Most of the anachronistic technology, such as a high-speed airship, is behind the scenes.

Every time I thought something might be historically incorrect, I checked it, especially “public” technology and language. I took pains to make sure no one was using a 20th or 21st century expression. One exception is the expletive “wanker,” used by Crowley, that dates from the 1940s (in print), which I decided to use anyway because it conveyed the feeling I wanted. (One reviewer on the website LibraryThing claimed I was adding historical details only to “show off” my research rather than advance the story, but gave no examples of the allegedly superfluous details.)

I dispensed with accuracy in the case of certain biographical details, of course. There’s no evidence I know of that Crowley and Tesla ever met in real life, and a lot of the advanced technology I attribute to Tesla in the book isn’t necessarily stuff the real Tesla made, such as a metal detector and a taser. And as far as I know, Aleister Crowley never levitated naked up the side of Devils Tower in Wyoming.

Q4: Crowley and Tesla were just a delight to see interact with each other! Where did this idea of chocolate consumption for heightened clairvoyant powers come from?

O’Keefe: I actually don’t recall (ironically!) exactly how I came up with eating chocolate as a way for Crowley to recall a crucial lost memory. There is a scene in which Crowley is trapped, mid-teleport, in a bizarre environment. I came up with that first, then decided that Crowley had forgotten the incident, but needed to remember it, and I struck upon the taste of chocolate as a kind of mnemonic.

I think of Crowley and Tesla as a kind of oil & water mix, a speculative fiction “odd couple,” and when I came up with the idea for the book, it surprised me that (as far as I knew) no one else had ever put them together in a novel. I think there might be one other novel out there with the two of them (I can’t remember the title), which I learned of after I started writing The Spirit Phone. And I think Crowley shows up in one issue of the comic Herald: Lovecraft and Tesla.

There’s no evidence the two met in real life, though they were both living in New York during World War I.

Q5: all throughout the story we read how Crowley and Temple use these grids to summon ‘familiars’. Tell us more about that.

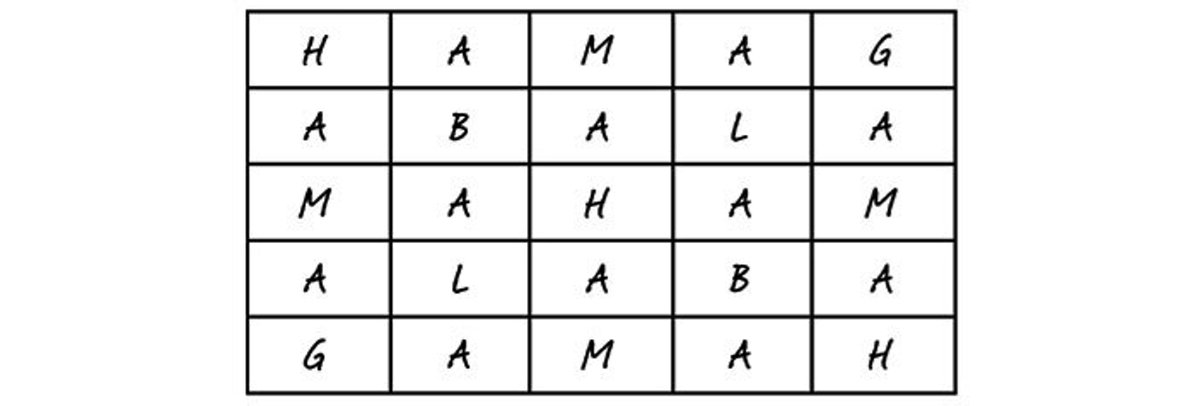

O’Keefe: In hindsight, maybe I should have called them talismans instead of “grids.” They are taken from a book of magic titled The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, aka The Book of Abramelin. It’s thought to date from the 15th century, but the original publication date is unclear. The book was used by Aleister Crowley in real life, so I decided to draw upon it.

There were already German, Hebrew, and French editions of Abramelin when S.L. MacGregor Mathers, an associate of Crowley’s, translated it into English. Mathers’ translation was published in 1900. The book was used by Crowley early in his occult practices, in particular at Boleskine House, his estate in Scotland near Loch Ness. There are even rumors that Crowley called forth the Loch Ness Monster.

The talismans (“grids” in the novel) are said to be a means to accomplish various feats of magic. Every use in the novel corresponds to a claimed use in The Book of Abramelin. For example, when Crowley summons the demon (or familiar) Lirion so that she can interrogate a spirit trapped within Edison’s spirit phone prototype, he uses a talisman described in The Book of Abramelin as used “To know Secret Operations.” When the demon-familiar Ashtaroth is summoned to try to get rid of a massive lump of magnetite that is causing an emergency aboard the airship, the talisman used is one described in Abramelin as meant to perform “Chemical labours and Operations, as regardeth Metals especially.” Similarly, the names of all three demon-familiars depicted in the novel–Lirion, Ashtaroth, and Elerion–are taken directly from The Book of Abramelin.

This was another point where “historical accuracy” had to give way to the demands of the plot. In The Book of Abramelin, the magical operations described are often time-consuming, meticulous, and ceremonial, but I wanted something more dynamic and fast-paced. So I just have Crowley write out a grid and call the demon, boom.

Q6: you and a few other authors like Bonsart Bokel are redefining modern fiction by using a different approach. Alternate history in the last few years’ mainstream has been, frankly, a joke. But you guys are exploring realms that are opening ground for new and compelling literature. What are your thoughts on this approach?

O’Keefe: Well, I tend to read more “widely” than “deeply,” and I can’t say I have a take on any recently published alternate history fiction. Those works which have inspired me are from the 20th century. For example, Harry Turtledove’s The Guns of the South, Gibson & Sterling’s The Difference Engine, and Len Deighton’s SS-GB (which is alternate history but non-science fiction). Then there’s The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick, which depicts a novelist living in an alternate timeline who writes about “our” reality as an alternate timeline. I think the original alternate history novel depicting the introduction of advanced technology into a past era is actually a 19th century work: A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court by Mark Twain, though it is not usually seen as “speculative fiction.”

I think of The Spirit Phone’s premise and particular mix of historical characters as its distinctive points, but if I’m opening up any new ground beyond that, I’m happy. Maybe it’s also that the occult and technology both feature prominently, either separately or combined, though I don’t think I’m the first writer to try that.

While alternate history is one aspect of The Spirit Phone, I think of it as a cross-genre work combining elements of horror, science fiction, science fantasy, murder mystery, and action-adventure. (Locus Magazine calls The Spirit Phone a historical fantasy. I have no objection to the label.) When I started writing the book, I didn’t think, “I’m going to write a horror novel,” or “I’m going to write a science fiction novel.” It was more like, “I want to write a novel with lots of weird stuff happening,” and added whatever elements I needed to make it so.

Q7: The Spirit Phone seemed to be a complete story. So what can we expect next from Mr O’Keefe? Will the Crowley/Tesla team be somehow reunited? Or any new projects you can tell us about? I think I can speak on behalf of VP and all of our readers and we definitely want to see more of these legends in the making!

O’Keefe: My current projects are: an English punctuation style guide for a publisher in Japan (which is nearly complete); an essay on Aleister Crowley’s poetry collection Alice: An Adultery, which will be partly based upon an article I wrote on Crowley’s visit to Japan in 1901; and a second novel which may or may not be a sequel to The Spirit Phone. It’s very much in flux at the moment.

What a fantastic premise for a novel! I’m eager to check this one out!

Does sound pretty cool. Thanks for stopping by, Sarah.