In the previous chapter reveal, I mentioned why some chapters needed heavy tweaking and sometimes I had to write entirely new transitional chapters while making Paradox (paid link) episodic.

Here’s the new opening chapter of Book 3: Defying Fate:

We exited the church from youngest to oldest—Debbie, Lana, Wyatt, Me, Mami, and Dad. Well, it seemed to be in age order, anyway. Technically, Dad and I were the youngest, We wouldn’t be born for decades, but my mother and siblings didn’t know that.

Okay…biologically speaking: they weren’t really my parents and siblings. “Dad” was really my uncle. I was not related to Mami other than through unofficial adoption, and not related to the kids except through Dad. Confused yet? Just wait.

Other people, dressed in their Sunday finest, smiled and bid us goodbye, tipping hats or waving. Mami responded to each, cheerfully. Dad tipped his own hat and replied as if conserving the energy it took to move his mouth. Debbie would have taken off running to who-knew-where, had her older sister not held a firm grip on her hand.

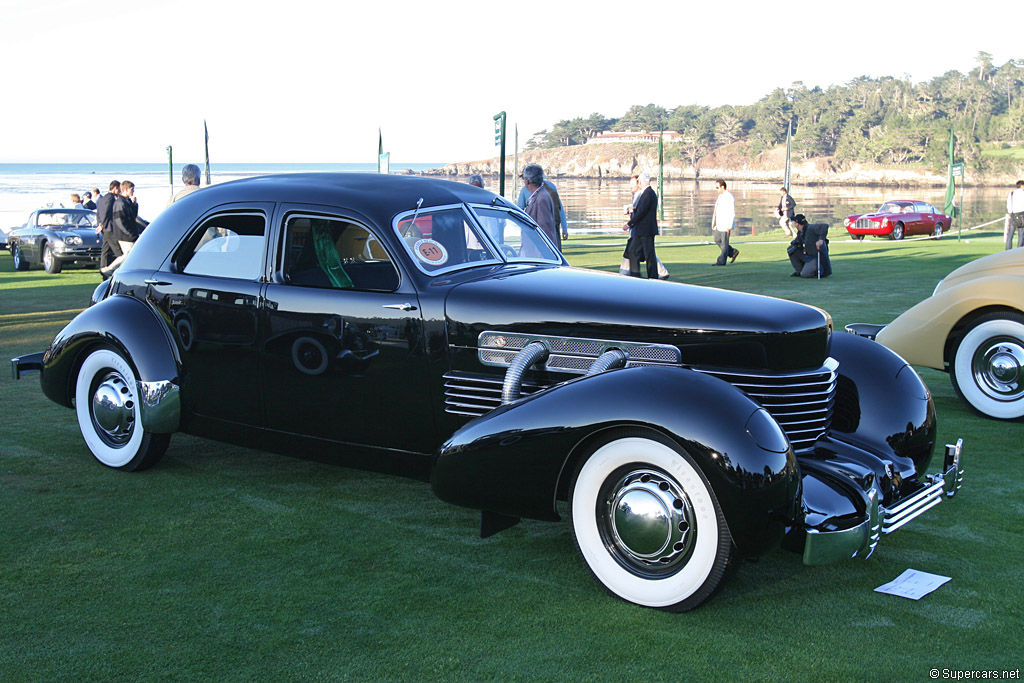

We strolled across the parking lot to Dad’s yellow ’37 Cord. Dad opened the passenger door for Mami. Then came one of those fascinating feminine maneuvers she was so adept at: she whirled so that she faced away from the open door and fell slowly backwards into the seat. While on the way down, the hand not holding her purse reached around behind her and pressed against the fabric of the new dress Dad had just bought her, sweeping it over to pull taught against the back of her thighs right before her rump hit the seat. It was timed perfectly so that her hand cleared just before getting caught between the car’s seat and…ahem…her seat.

I herded the kids into the back seat behind Dad, then I climbed in behind Mami. Dad cranked the engine to life.

“Sweet music!” Wyatt exclaimed, grinning at the Cord’s bass rumble.

As with most of Dad’s vehicles, the Cord’s powertrain was far from stock, and almost 50 years anachronistic. He and I had built the engine and transmission in 1986, in a garage at Texas Station—one of Dad’s many properties scattered strategically across the post-Industrial Revolution region of the space-time continuum. He sunk it in gear and got us rolling.

Mami leaned across the front seat and kissed him on the cheek. “Thank you for taking us to church, my love.”

He turned his head and grinned at her.

Dad didn’t care for organized religion, But he did care for Mami, and was willing to sit through Sunday services to please her. I found myself wishing, for the thousandth time, that he would give up his other lives, his mistresses, all his mad scientist schemes, and just settle down with Mami. Keep her happy full-time.

At this point in my life, I could understand him wanting to have a life and a squeeze at every time-space coordinate. I was spinning plates of my own, by then. But if Mami was ever to find out Dad was playing house with other women, it would break her heart.

She half-turned, craned her neck, and made eye contact with Wyatt, who sat on the edge of the back seat, his hands gripping the front seat on either side of Dad’s neck.

“You are just like your father,” she said. “You both like loud things.” Then she tried to imitate the exhaust note with her voice.

My sisters giggled at her impression, but Wyatt rolled his eyes. My Spanish had improved to the point I could follow these conversations without missing anything important.

“Oh, are you too grown up for my engine noises now, Mijo? It wasn’t that long ago when you would laugh, too.” She tried some more sound effects, then turned to her daughters and declared, in English, “The only difference between men and boys is the eh-size and expense of their desired toys.”

Lana and Debbie giggled some more. Maybe they understood everything, maybe not—but they knew Mami was acting silly and teasing Wyatt.

Dad arched an eyebrow and threw a sidelong glance over his shoulder toward me. We exchanged a grin. The Cord purred along at 70 miles an hour.

“Vroom! Vroom!” Mami continued, and apparently her sound effects were never going to get old for the girls.

When we arrived at the Orange Grove, Dad parked by the front porch and asked me to put the car away. He walked around to open Mami’s door and give her a hand climbing out.

Wyatt let himself out, then held the door open for his little sisters.

As my family went inside, Dad turned back toward me as I slid behind the wheel. “Meet me at the temperature wheel when you get changed?”

I nodded, and steered the Cord over to the enormous building comprised of several garage bays and a few aircraft hangars. Bays in the building were kept locked, ostensibly to discourage any thieves who ventured all the way out to the Orange Grove to see what they could steal. The more compelling reason was that Dad kept some stuff here that had not been invented or manufactured yet. I parked and locked the swing-up garage door before strolling to the hacienda to change.

It was hot at the temperature wheel and Dad probably wouldn’t ask me to meet him there if there wasn’t some maintenance required. I dressed in my “greasies”—jeans already so stained by petroleum products that they shouldn’t be worn in public, and an equally ruined sleeveless shirt (“undershirt” at these coordinates, “muscle shirt” or “wife-beater” in the era I came from).

As I drew near to where the temperature wheel and generator (really an alternator) were housed, a rhythmic scraping/grinding noise grew more prominent in the ambience.

The outer building looked like a large barn, but once inside, it was obvious that it had no roof—flat or otherwise. All it had was a fairly narrow arch spanning from one wall to the other. The sun shone directly down into the vast space. Lining the walls were sturdy steel shelves loaded with banks of nickel-iron batteries, each larger than a footlocker. The huge alternator sat at the south end of the structure, turning quietly while providing electricity for the hacienda and the rest of the estate. Attached to the power source was a gearbox. The spinning shaft driving the gearbox extended through a hole in a small greenhouse in the center of the huge “barn.”

I entered the greenhouse and the sweltering heat blasted me. Dad was already inside, sweating buckets. What drove the shaft was the temperature wheel. The outer band of the wheel was composed of multiple airtight tanks, with pipes leading like spokes from each tank to a central hub surrounding a circular housing from which the shaft extended. The top third of the wheel extended up through a slot in the greenhouse roof, rotating under the arch across the top of the barn—so that it was always in shade, but exposed to the breeze. The bottom of the wheel sat in a metal trough full of water kept hot by the ambient heat of the greenhouse. Inside the tanks and pipes of the wheel was freon—which transformed from gas to liquid form just from a few degrees change in temperature. It was heated into light gas form down inside the greenhouse, expanding up through the pipes into the tanks. Up in the shady breeze, the gas cooled inside the tanks, transforming to heavier liquid. The weight of the liquid caused gravity to pull the tanks back down, and the wheel turned. It rotated slowly, but with massive torque. The torque was overdriven in the gearbox so that the alternator spun fast enough to generate scads of electricity.

The scraping/grinding noise was loud here inside the greenhouse. Dad, dressed much like me, stooped over next to the central housing, opening a toolbox.

“Okay,” he said. “This should go quick with both of us. You know what that noise is?”

“A bearing gone bad?” Even without him honing my mechanical aptitude over the last several years of relative time, I would have known the sound was caused by friction, and the repetitive nature of it meant it came from a rotating part.

Dad tapped his temple and nodded approvingly at me. He looked up at the bright sky visible through the slot in the greenhouse roof. “Now, we could wait until after dark, when this thing stops spinning anyway, but who wants to do this at night? Engage the clutch, if you would, Ike.”

I pulled a large lever from vertical to horizontal, and pinned it in place to hold it down. As the clutch engaged, the wheel spun faster, while the shaft spun slower and came to a stop after a few moments. The awful noise stopped with it.

Thankfully, the bearing for the wheel itself was fine, or we would have had no choice but to work on it in the middle of the night. That wheel was going to spin as long as the sun and breeze caused the temperature disparity. There was no stopping it until after the temperature disparity ended.

Inside a cardboard box decorated with black handprint stains was the replacement roller bearing, which Dad had already packed with grease. Dad and I chatted while we worked together to get the old bearing out and this new one in.

“What did you call your pals there at Poly, again?” Dad asked, with an amused expression.

“The Tumultuous Trio,” I said, also amused, just thinking about my college roommate and the two other upperclassmen who had begun football training camp hazing me, but had since more-or-less welcomed me into their clique. “Wherever they go, it’s like a storm hits whoever is there.”

“Rowdy, I guess?”

I chuckled. “Well, there’s Bartok—offensive lineman. Intelligent enough, but still…yeah, rowdy. He’s about the size of Godzilla. His footsteps make the ground shake. He also likes to mess with people. Has a dry sense of humor.”

“Big corn-fed boy,” Dad remarked, nodding, still amused.

“And my roommate, Gartenberg. He’s like the straight man for the other two’s comedy routine, quite often. Zeppo or Gummo, I guess, playing off Chico and Harpo.” I considered this assessment for a moment, then corrected myself. “Well, sometimes he can be like Groucho, actually. He’s got a dry sense of humor, too. Vicious wisecracks and comebacks, sometimes. Probably the smartest guy on the team.”

“What position is he, now?”

“Flanker,” I replied. “He also plays guitar and sings. He introduced us to this beatnik bar not far from campus. Weird crowd—they snap fingers for applause instead of clapping. They’ll actually sit and listen to freestyle poetry and seem to enjoy it.”

“It’s gonna get even weirder in the ’60s,” Dad said. “You’ll see.”

“Then there’s Kiley,” I continued. “Linebacker. Solid muscle—including between his ears.”

Dad grinned.

“A redneck, with cowboy hat, cowboy boots—the whole rig. He’s the most hilarious of all, but I wouldn’t say he even has a sense of humor.”

Dad cocked an eyebrow at me.

“As near as I can figure,” I said, “life for him is just one ongoing phallic comparison chart.”

Dad busted out laughing. He didn’t do that very often.

“Gartenberg said one time that Kiley isn’t even human—he’s a walking, talking penis. And…yeah…he might be right. Outside of football, penis size seems to be all he thinks or cares about.”

Still chuckling while recovering from his guffaw, Dad remarked, “And he’s got the biggest one ever, I’m sure. Seven feet long, or so?”

“Oh, nobody in the whole history of penises was ever hung as heavy as Kiley,” I assured him. “Just ask him—he’ll tell ya. It would shatter his whole world if he ever found out different. I mean, he literally seems to have no other interests in life. Gartenberg and Bartok are hot-rodders. But ‘hot rod’ means something else entirely to Kiley.”

Dad shook his head. “On a serious note: isn’t it amazing that most young men knew how to work with their hands once upon a time? Get past 2000 or so and they can’t even change a tire or give a jump-start. Cruising, racing, wrenching—it was all part of the culture. Then somehow it went to playing videogames and surfing porn. Yay, progress.”

“I know which culture Kiley would find superior,” I quipped. “But yeah: the most popular hobby, by far, is modifying cars. Roomie’s got a T-bucket. Bartok’s got a chopped-and-channeled ’49 Mercury.”

“Classic lead sled,” Dad declared, nodding, still grinning.

“They were talking smack about the Studebaker, so we drug it on out to a lonely road nearby, and I blew their doors off. I guess that’s part of why they eventually seemed to give me some respect.”

Dad sobered. “Remember what I told you about keeping a low profile.”

“Yes sir. I sandbagged so that I just barely beat them. Wouldn’t let them look under the hood. I explained the fat tires by borrowing your cover story about secret research-and-development prototypes.”

“Don’t ever forget we’re taking a serious risk,” Dad said, frowning now. “The Erasers don’t just come after troublemakers who split the timestream. They murder temporal fugitives, refugees, temporal tourists…anything they find that doesn’t belong, they eliminate. I still don’t know how they found you in St. Louis, and that goes to show you they have resources we don’t understand, yet.”

The Erasers had murdered my biological family back at my native coordinates in 1988.

Back in the future.

“The continuum is a gigantic haystack,” Dad continued. “The TPF…the CPB…they have limited resources and can’t find every single needle. We don’t want to help them get lucky.”

TPF stood for Temporal Police Force, which Dad once worked for, but deserted to become a time-space fugitive. The CPB was the Continuum Protection Bureau—the TPF’s parent company. The Erasers were an elite, clandestine hit team from the TPF.

“Hot-rodding is good,” he continued. “Playing football is fine. Those help you blend in—to a point. But if too many people find out how fast your car is, that could start a buzz. If that buzz reaches the ears of somebody working for the CPB, your new identity will be targeted. And if there are photos of you available, that just makes it easier.”

I skipped Picture Day every year in high school, at Dad’s urging, so there would be no visual reference of me in the yearbook. I was in the group photo of the football team, but Dad had somehow gotten access to the negative before printing, so that there just happened to be a blemish in the film where my face was.

Dad and I had built the Stude together. The suspension and powertrain were composed of parts from decades in the future. It was much, much faster than any other street legal vehicle at my adopted coordinates…with the exception of Dad’s ’41 Willys. So much faster, that anyone with knowledge of a particular data set might decide it was an anachronism, and that its owner was a person of interest.

“Yes sir,” I replied. “I was careful, like I said. And I’ll stay careful. But how many CPB assets would even know enough about street racing to…if they somehow learned everything about it…decide the Stude doesn’t belong where and when it is?”

Dad shrugged. “Probably nobody—though there is this tool called the Internet. You may have heard of it.”

The Internet and World Wide Web were unknown to Joe Public at my native Coordinates, and earlier. But I had been introduced to it in trips to BH (Brazilian Highlands) Station in the 2000s.

“Okay,” I said. “But wouldn’t they have to know a lot even to research the right information online? I mean, they’d have to know smoke when they see it, before they start looking for the fire.”

“Listen, Hero: this is not a situation wherein you want to live out on the edge, seeing how much you can endanger yourself and get away with it. You might be able to step out to the very edge of the cliff and not fall over, but you need to stay far, far away from the cliff so no bad actor can push you over.”

When he called me “hero,” it was best that I just kept my mouth shut and listened.

“When you’re young and in great shape, you assume you’re invincible,” Dad went on. “But the Cabal has assets that can kill you like that.” He snapped greasy fingers to make his point. “When you don’t even know you’ve been targeted. Don’t ever try to defy Fate. Do whatever you can to avoid even drawing her attention.”

It was normal for Dad to personify fate. He spoke of it as he would some heartless, sadistic femme fatale.

Dad might be eccentric by some measures, but he was far from delusional. Neither was he superstitious. Yet he believed there was some supernatural or paranormal being who shadowed his every step, waiting for opportunity to pounce and visit disaster on his life. By escaping to different coordinates, Dad made it harder for that entity to track him. And me.

Sometimes I found myself adopting that same personification of Fate. Especially when I thought about my past life.

***

We got the new roller bearing in and put the machinery back together, then returned to the hacienda to clean up for supper.

Mami had roasted a chicken, fried potatoes, baked bread and sauteed vegetables. Again, out of respect for her beliefs, Dad said a prayer of thanks and asked a blessing on the meal, to a God he didn’t see as merciful, like she did. He might not have even believed He existed—though he did occasionally mention God, in a speculative way.

“I heard the Germans attacked the Russians,” Wyatt said, around a mouthful of potatoes.

“Don’t talk with your mouth full,” Mami warned him.

Wyatt swallowed his food and said, “I thought they were allies.”

Dad nodded. “The USSR was part of the Axis for a while. Remember: they both invaded Poland.”

“Why did the Germans attack them, then?”

“It was bound to happen,” Dad said. “One of them was going to betray the other one, sooner or later. Hitler wanted to strike first, before Stalin’s numerical advantage could be fully brought to bear.”

“Why?”

“The National Socialists want ‘lebensraum‘,” Dad said. “Space to live. They need real estate for their population to grow, so their empire will last a thousand years—and they think the best lebensraum is to their east. The International Socialists, on the other hand, want the entire world under their system, as Marx envisioned it. Expanding into eastern Europe is a good start.”

Wyatt looked confused. “If both Germany and Russia attacked Poland, how come the Allies only declared war on Germany?”

Dad smiled at his son. “I want you to remember that question. Almost nobody has the guts or the brains to ask it. Maybe one day we’ll have the answer. And the answer might just be the same answer for most of the other questions about this ‘great crusade’.”

“Are we gonna join the war, Daddy?” Lana asked.

Dad nodded. “Yup.”

“Why?” Mami asked. “It has nothing to do with us.”

“Roosevelt wants us in the war against Germany,” Dad said. “Just like Wilson did last time. He’ll figure out a way to get us in it. Remember: Germany isn’t the only Axis country. But they are the only ones living with the consequences of us joining the last war against them. Not everybody has learned that lesson the way they did.”

“You think I’ll be old enough to go fight the Germans when it happens, Dad?” Wyatt asked.

Mami gasped. “God be merciful! Why would you even ask that, Mijo?”

“You won’t,” Dad said. “And be careful what you wish for.”

“But didn’t you fight in the Great War?” Wyatt asked.

“No.”

“But where did you get all your scars?”

“Never mind that.”

“Will Pedro have to go fight the Germans?” Lana asked, with a concerned glance at me.

“Let’s pray he won’t,” Mami said. “And enough of these war rumors. Let’s talk about something pleasant and enjoy our time together.”

When we had finished supper, Dad gave Mami a shoulder massage while she supervised Lana and Debbie doing dishes, Wyatt went outside to lock the chickens up in the coop. When he returned, he switched on the radio in the parlor. After some humming and whining, we could hear the Ink Spots crooning “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire.”

That seemed to be the sentiment of most Americans at the time. And Mami.

Dad had been trying to dissuade me from military service. For now, football was enough to slake my primordial attraction to combat. And I didn’t doubt his warnings about Vietnam and the conflicts that followed. If Wyatt stayed in his native timestream, he would probably be sent to fight in Korea—which became the first obvious sacrifice of American blood on the altar of globalism. But I still felt a compulsion to be a fighting man.

Mami turned and gave Dad a wistful look. He took her by the hand and led her into the parlor. I drained my glass, set it on the counter next to the sink, and followed them.

My adopted parents danced as if they were the only two people in the world. Mami looked like she was in heaven, Dad looked pretty content, too.

The song ended and Artie Shaw’s “Frenesi” wafted out of the radio speaker. Now they laughed together and moved to the faster beat, with dance steps Mami had helped teach me.

I strolled to the library, retrieved a pulp magazine I had left there, returned to the parlor and sat on the couch to read it. While our parents danced, Wyatt brought in the components of a model airplane and resumed building it on some old newspaper he spread on the hardwood floor. When finished with the dishes, the girls also joined us in the parlor.

We all amused ourselves in different ways, but the whole family did it all together, at the same time and place. We preferred it this way. How different this world was, to the one I was born into!

The DJ read the script for a Blue Coal commercial, before playing the next record. The music got Mami right into the groove. A big, booming rhythm section blazed a boogie-woogie foundation and she shook her hips to the pounding beat of “Drum Boogie” by Gene Krupa’s orchestra. Debbie began laughing at Mami’s gyrations. Soon Lana joined in, clapping her hands in merriment. Even Wyatt began to snicker.

“Laugh it up, funny boy,” Dad told Wyatt, guiding Mami around the floor.

Watching games on TV was my preferred way to spend a Sunday evening—or playing videogames when it wasn’t football season. But I never felt as good after one of those entertaining Sundays as I did after times like this.

I bid my family goodbye a little later—taking Dad’s Packard, which I had used to make the jump here to the Orange Grove. When I had driven far enough along Dad’s private road that I wouldn’t be visible from the house, I engaged the warp generator.

Knowing what to expect made the jump seem like no big deal, but I experienced the same queasy feeling, the same brief visual distortion and sucking away of sound. When all my senses rushed back to normal, I was outside 1960 Bakersfield on a Friday afternoon.

I drove through town to the house I had lived in through junior high and high school. My Stude was sitting in the driveway. I parked the Packard in the garage.

Salvatora came out to greet me. I threw her up in the air, caught her, then bear-hugged her while blowing fart-like sounds against her cheek. She protested, but laughed despite herself. She was another of Dad’s kids who assumed I was her brother. Not half-brother or step-brother—the bona fide article.

Salvatora was five years old, now. I had been so busy doing my own thing that I hadn’t thought much about her. To see her innocent face was to feel joy. She had been speaking in full sentences for quite a while and seemed pretty bright.

“Guess what we finally got?” she asked, leading me by the hand inside the house.

“Mumps,” I guessed. “Measles. Chicken pox!”

She grinned and shook her head. “A television!”

“Wow,” I said. “Dad finally gave in, huh?”

“Well, he did something to it so that Mom can only watch certain shows. And I’m only allowed to watch when Mom or Dad let me. He wants me to read, and to play outside when I don’t have a new book.”

“What an ogre!” I said, tickling her.

Angelina came around the corner from the living room, greeted me with arms extended and a high-pitched squeal. “Welcome home, my college scholar!”

She was a Sicilian woman who spoke English with a heavy accent but was easily more gorgeous and shapely than any Hollywood starlet. Out of loyalty to Mami, it had been difficult for me to accept her being with Dad. Mami was still Mamita, and always would be, but Angelina eventually won me over. I shouldn’t think of her as “one of Dad’s mistresses.” She believed she was his wife. His only wife.

“Hi Mom.” I gave her a hug, lifting her off the ground, but quickly set her down, feeling a bit guilty and weird for noticing how attractive she was.

“I didn’t know you were coming back this weekend,” she said. “And so early! Please tell me you didn’t speed all the way to get here.”

“My classes ended early today. I wanted to check in on some of my friends. Go cruising tonight and tomorrow.”

She glared an icy look at me, placing one hand on her hip. “What a thing to say!”

Salvatora bit her lip and grimaced. “No Isaac, you came here to see us.”

“Okay,” I said. “I came here to see you.”

Angelina looked nothing like me, with her dark hair, dark eyes, and dark complexion. But surprisingly few friends or neighbors ever mentioned it. I did bear a strong resemblance to Dad, so maybe folks assumed his genes were dominant in me. For her part, Angelina never referred to me as anything other than her firstborn son. She had been conspiring with Dad and me to perpetrate my cover story for so long, she might have forgotten it wasn’t true.

Looking at Salvatora, it was easy to assume we were siblings, since she had high cheekbones like me and a (less-pronounced than mine) hump on the bridge of her nose.

“When is your father getting back?” Angelina asked.

“I assume tomorrow night. He’s been working on a generator at one of his properties.”

She nodded. She knew he owned lots of real estate and spent a lot of time at different places running different business ventures. That was technically true, just as my comment about fixing a generator technically was. What she didn’t know was that his properties were at several different coordinates in the continuum, and he had a diverse harem scattered around time and space with them.

I sometimes speculated that Angelina came from a Mafia family. It might explain why she didn’t ask questions about Dad’s business and would probably take what secrets she did know (like about me not being their child) to her grave.

We ate supper at six, like normal. Then I drove my Studebaker down to the Strip.

With windows down and rock & roll blaring from car speakers, I joined the unofficial two-way parade forming at dusk along the main drag. Most businesses were closed, but the business of youth was just getting started. Nearly every teenager in town was cruising the Strip just like me.

Of course, I was still a teenager too, even though off to college during weekdays. I was rare for being a college student back home this time of year, and also rare for being alone in my car.

Every teenaged boy with a functioning automobile and a driver’s license was piloting something up-and-down the Strip at some point that night: hot rods, lead sleds, street machines…or sometimes cars borrowed from parents. Those without wheels, or too young to drive, crowded in front and back seats around somebody who could. They joked and yelled to each other through open windows; leaned against fenders in parking lots shooting the breeze; sat in their cars at Burger City or other drive-ins eating and drinking sodas. Most of them were cheerful. Some were rowdy.

I took in the scene academically at first. Dad once quoted an old axiom about eras and generations to me:

Hard times create strong men.

Strong men create easy times.

Easy times create weak men.

Weak men create hard times.

Back at my native coordinates, weak men controlled society’s institutions. Having visited the relative future from then, I knew that those weak men would, in fact, create hard times. But in 1960 Bakersfield, we enjoyed unbelievably smooth sailing. Strong men had survived the Great Depression and World War Two, then built an idyllic paradise for their children to inherit.

Bakersfield was what it was because of the exodus of migrant workers escaping from the Dust Bowl a generation ago during the privations (some with natural origins, but most man-made) of the New Deal. Most of my carefree teenage peers were children of desperate men who had to scrape and claw their way to a living, who usually couldn’t afford a car of their own, much less burn gas on purpose cruising. And they had worked too long of hours on the farms and oil fields to party every Friday and Saturday night.

The word “teenager” wasn’t even invented until my adopted generation came along, with their allowances, their own cars, freedom from labor in the family business, and a still relatively free market dreaming up all sorts of products that catered to their every whim.

My analytical train of thought kept getting interrupted by people waving and calling to me from open car windows. I hadn’t been gone so long that they had forgotten who their starting quarterback had been. I waved and called back.

Most of these offspring of Okies had their car radios tuned to KUZZ, which played country-western, honky-tonk, and rockabilly. I was one of the rebels, who preferred Ross “the Boss” Beaucamp and the records he spun on KDIG.

“Dig it on the K-Dig,” Ross the Boss was saying, as I eased to a stop at a red light. “Elvis Presley may be gone with the draft, but his tunes still send us. Now I’d like to remind you—”

A blue ’55 Chevy pulled abreast of the Stude and I could feel somebody staring at me. I turned my radio down to hear the Chevy’s engine as I craned my neck to look. By the sound, the overhead-valve V-8 was a little warmed-over. I also heard Charlie Rich trying to sound like Elvis singing “Lonely Weekends.” Obviously, the son-of-an-Okie at the wheel had his radio tuned to KUZZ. He and his passengers regarded me with stony faces. He revved his engine. I stared back and revved mine. I recognized the driver and one passenger from somewhere. Maybe they had been sophomores or juniors during my senior year.

Neither of us said a word to each other. We didn’t need words to know that when that light turned green, we were gonna floor the gas and see who could make it to the next red light first.

The light turned green. Our engines roared. The Stude squatted down and shot forward, laying twin patches of rubber as I banged through the gears. The Chevy was outclassed in every way. Even the rear end was a one-legger. He just couldn’t match the power I applied to the pavement. I blasted through two intersections before a red light caught me and I had to brake hard, setting the Stude down on its nose at the crosswalk. I checked the mirror. The Chevy decelerated rapidly and screeched around a corner onto a side street. As it turned, an arm shot out the window, flipping me the bird.

“Yer mama, Jaeger!” a voice echoed down the street.

I guess not everybody who remembered me was a fan.

A yellow ’48 Ford rolled to a stop next to me at the stop light. A chorus of voices cheered. Melvin Jurado and some other Pachucos I remembered grinned at me.

“What’s up, Jaeger?” Melvin greeted.

“Mel!” I called back. “Long time no see!”

“I’m glad I was here to see that,” he said. “Kenny’s been bragging about that ’55 ever since you left town, man!”

“It turns corners behind me and sneaks away real good,” I replied.

He nodded with a toothy grin.

The light turned green and we eased through the intersection, keeping pace so we could carry on our conversation through our open windows.

Melvin pointed at the pimple-faced boy in the passenger seat. “Man, I was just telling him when we saw you: can’t nobody in town beat you. You’re still the champ!”

“You still running a flathead?” I asked, knowing the answer already from the sound.

“Yeah, but I’m building an engine I got from the junk yard. You just wait, Jaeger: when I get everything ready, I’ll come looking for you!”

“Okay, Mel. You better weld your doors on.”

“You wait, Jaeger—you’ll see. Hey, watch out for Pierce! Last we saw him he was hiding in that alley beside Wheeler’s!”

Pierce was one of the cops who prowled the main drag on weekends, looking to hand out citations to young people doing what I had just done.

A few more minutes and I became separated from Mel in the traffic. As I passed Burger City, somebody cried my name. I craned my neck to scan the parking lot as I passed. My eyes barely had time to register a waving arm and long blonde hair.

At the next opportunity, I whipped around and headed back toward Burger City. I parked right next to the convertible Buick the blonde was leaning against. Two other girls were with her and they all covered their mouths and tittered, glancing at me and each other. The blonde looked familiar but I couldn’t place her.

“Mule Skinner Blues” was blaring from all the radios turned to KUZZ. I shut down the engine, opened the door and walked over to the girls. Their nervous mannerisms intensified as I drew close.

“Hi,” I said.

The blonde bit her lip, smiling, looked away, then met my gaze. “Howdy, Ike.”

The closer I got, the younger she looked.

The other girls greeted me, bashfully, but I concentrated on the blonde. “Do I know your name?”

In the lights of the Strip, I thought she blushed. “It’s Dinah.”

“Your face looks familiar.”

“I’m Kip’s sister.”

“No kidding? Oh, hey. No, I see the resemblance,” I said. “I remember, now. How old are you?”

“Fourteen. How old are you?”

I exchanged small talk with her and her friends for a few minutes, but then found somewhere else to be. They were just too young.

I cruised some more.

This was the social network in postwar America. There was a sort of addictive zeitgeist to it, too.

The cheery, boisterous vibes were infectious. Everybody was here to socialize and have fun. Some pursued fun by street racing. Some by pulling pranks on others. Some by gossiping. But by far, the most popular way to seek fun was by flirting, and making time with the opposite sex.

Nobody batted an eye at all the money or time being wasted. The country wasn’t in a depression or fighting a war—just the opposite. Nobody was worried about where their next meal was coming from, or if they or their fathers or brothers might be killed overseas. The worst problems in this universe would be getting grounded, suffering a flat tire, or failing to find a date.

Easy times.

Brenda Lee’s “I’m Sorry” warbled out of radios all along the street until I got to Hep Shakes—Burger City’s primary competition. There, radios were turned to KDIG. I parked and strolled over to the pay phone. I called Blanca’s house and got her mother, who told me she was out.

I approached the walk-up window, dodged a car-hop, and heard Rosie and the Originals’ “Angel Baby” blare out of the nearby radio speakers. It was then that I noticed about half the crowd at Hep Shakes was Hispanic.

The world stopped as every Chicana sang along, and every Chicano either sang or bopped along, too. It was like a trance or something.

On Oldsmobile pulled up to an order stand. It was packed full of Latinas, and every single one of them was singing “Angel Baby” along with Rosie. They remained in the car and made no move to get out until the song was over. Then there was a collective sigh, the doors opened, and the girls spilled out. Three of them mobbed to the restroom, jabbering all the way.

I ordered a strawberry shake and a burger with fries, thinking I might take them inside and sit in something besides the Studebaker’s seat for a while. Once at a booth, I watched the scene outside. Now “Alley Oop” was playing and nobody was in a trance. The girls returned from the bathroom and I recognized Fatyma Benavides.

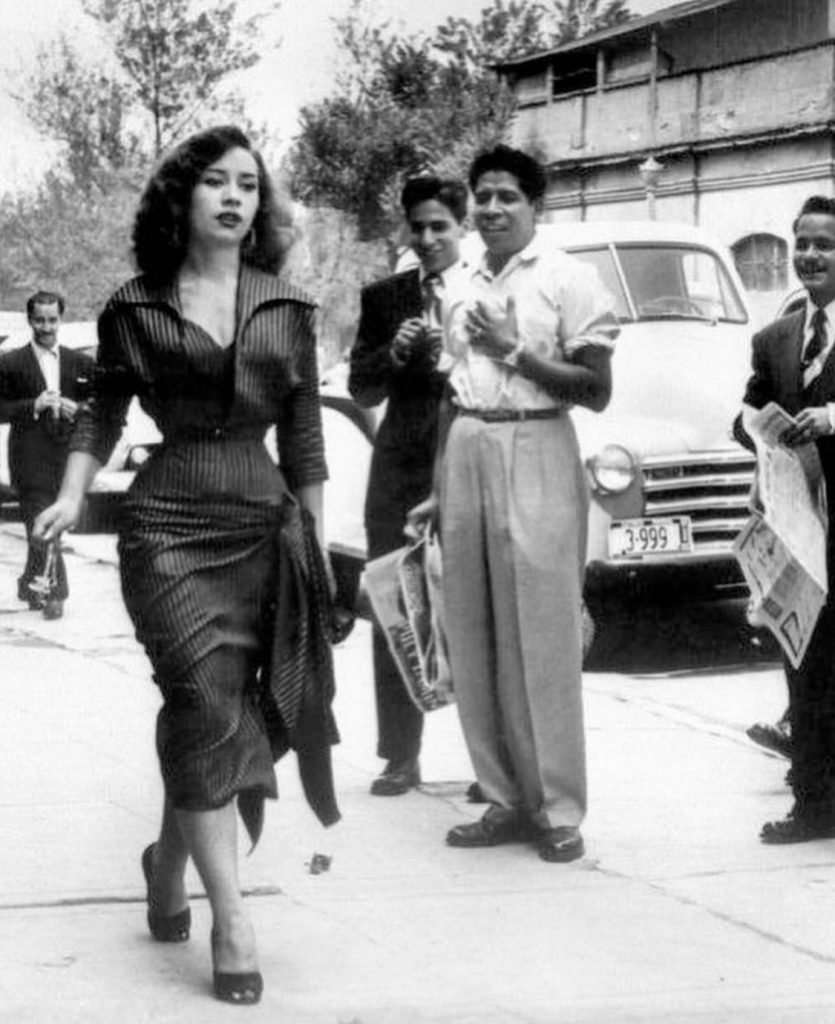

She was a year behind me in school, and a Top Tier scorcher. Blanca was also Top Tier, but with facial features that had a streetwise, cruel quality to them. Fatyma’s beauty struck me as of a more innocent, vulnerable flavor. I had wanted to ask her out for years, but we had never been between romances at the same time. I thumped the plate glass window with the heel of my hand until I got her attention.

She stopped in her tracks while, looking irritated, she turned to face me through the glass. She showed me the FGGE (Female Glare of Guarded Evaluation) before recognition registered on her face.

“Ike Jaeger?”

I wiped my mouth with a napkin, got up from the booth, and walked outside to meet her. That she waited for me was a good sign.

“I did not know you were in town,” she said as I approached, with a musical lilt in her voice.

“Here for the weekend,” I said. “What are you up to?”

She shrugged. “Me, Delores and the girls are just hanging out.”

“Ain’t that kinda’ crowded?”

She clasped her hands behind her back and twisted at the waist so that her shoulders rotated one way, then the other. Her head was tilted slightly downward but her eyes rolled up to stay fixed on my gaze. “Why it is crowded?”

I had learned the customs and rituals of postwar cruising pretty well over the last few years.

Not everybody wanted to admit it, but everybody who wasn’t already dating somebody hoped to meet somebody and hit it off. (Of course, some who were already dating wanted to meet somebody new and jump ship.) Some were lonely. Some were hurting or humiliated from a break-up and didn’t know what to do by themselves. Some were jealous of friends who were with somebody, or of the person dating their crush.

Pride and yearning met at the intersection of Irreverence and Hilarity. Most amorous teenagers at these coordinates masked their insecurity by hanging out with a group. They covered their desperation with forced mirth. They laughed at everything—including a lot of stuff that simply wasn’t funny. That was all part of showing the world that they took nothing seriously. To be without a date was pitiful, they assumed, but to be sad or angry about it was worse. So they clung to their cliques and pretended to be above it all. Everything was funny, and they fed off each other’s fake amusement. Sure, we don’t have dates—because it’s just not that important to us! Can’t you see that we’re just enjoying life? Why—you don’t want to go out with me, do you?

Still, some were, due to various circumstances, unable to cruise as part of a group. The bravest of them came to Cruise Night anyway, alone. Girls rarely did anything alone, but once in a while, they put themselves out there with no backup. As a rule, such girls were Tier Three and lower. But a bad breakup or other scenario could make even the most attractive girls desperate. They would use timing and trajectory to cross paths with a boy or group of boys, hoping one (the “cutest” one, of course) would make a pass. But she had to be cool while presenting herself as bait. The safest demeanor to adopt was distraction. She was just so preoccupied with walking to some destination (or ordering a shake and fries, or window shopping at a closed store, or making a call from a payphone) that she wouldn’t even notice if you didn’t chat her up. And if you did feed her a line, she might even pretend not to hear so you’d have to repeat yourself.

Cruise Night was kind of like a talent show, but everybody was performing from a repertoire of just three or four types of acts.

I didn’t mind coming alone—not because I was necessarily brave, but simply because I knew from experience that the stigma of being dateless was self-imposed and mostly imaginary. As long as you weren’t creepy or awkward, or clueless at talking to girls, getting dates was easier this way. It would be even easier for solo girls, but fear and self-awareness kept most of them from taking the easy path.

“Well,” I told Fatyma, “I have an empty passenger seat. Not crowded at all in my car.”

She cocked her hips and twisted her mouth in a sort of skeptical smirk that suggested I wasn’t trying hard enough.

“You hungry?” I asked.

“For why?”

“‘Cause I was about to have a bite. You could have one with me, my treat, and maybe go for a ride with me afterwards.”

“The slick football star,” she said, with a grin that was now hard to read. “This is how you pick up all the college girls?”

“Naw. For them, all I have to do is show them my advanced anatomy textbook and wiggle my eyebrows. ”

“Ai-yai-yai!” She seemed to be genuinely amused, now.

“How ’bout it?” I prodded.

“I could eat something, I think,” she said.

I opened the door for her. We went inside and she joined me at the booth. After she had ordered, I asked, “So what happened to what’s-his-face?”

“You mean Juan? Broke up,” she replied with a win-some-lose-some gesture. “Where is Blanca?”

I shrugged. “I called. She wasn’t home.”

She nodded. “She could not shut up about you for a while. Now she say it is not so serious.”

“I guess it’s not.”

“You do this so much? Date girls you are not serious with?”

“Don’t tell me Fatyma: you’re one of those chicks who demands a proposal before you’ll agree to a first date.”

Her guarded expression finally lightened up and an easy smile spread over her face. “No. I am not so strict. Not always.”

“Are you gonna be tonight?”

“I am here talking to you, no?”

“Okay. Live a little.”

“Can I ask you something?”

“You just did.”

She rolled her eyes and shook her head as if exasperated. “Why me?”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, why me? All the other girls in the car. All the girls on the Strip tonight. Everybody knows all the gringas would jump to ride with you. Why me?”

“Why not you?”

“For real, Ike. I am serious. You never ask me out when you were at the school. But now you do. Why?”

“Because you’re not with Juan. Or Luis. Or Mianjel. You were always with somebody.”

“Me?” She shook her head and her already dark complexion got darker. Like she was blushing.

“I saw you walking from school once, my junior year. I saw in my rear view mirror—I had already passed by. I thought, ‘I should go offer her a lift. I should U-turn and go back and offer’. But I thought, ‘Nah, just keep going… ‘”

“You did not!”

“‘Nah, that’s a creep move—it’ll scare her. Well, she’s walking alone, so maybe she’s between boyfriends. Nah, I don’t think she likes gringos.’ So I just drove on down the street.”

“Between boyfriends!” she cried, covering her mouth and taking a swipe at me. She wanted to feign outrage, like I had just called her a slut, but was having a giggle fit.

“I figured I’d see you at your locker the next day during passing period, as usual, and I’d make the offer that day. But when I saw you, ol’ Luis was talking to you, and you were making eyes at him.”

“What? No. Nuh-uh! You are too much a liar, Ike.”

I placed one hand against my chest and held my other hand up so that the palm faced her. “Cross my heart. Scout’s honor.”

“You are playing with me, I think. Really, Ike? You swear?”

I showed her my index finger, put on a solemn expression, rose from the booth, and marched to the juke box. I dropped a dime in, selected “This I Swear” by the Skyliners, and watched her as the record began to play. She busted out laughing when she recognized the song, then shook her head at me as I returned to the table.

I’m pretty sure she was flattered, but concealed it under a big show of disapproval because I was acting silly.

And I was. But girls liked silly behavior in certain contexts.

“So, you were scared of Luis?”

“I didn’t think you would just dump him for me,” I said. “Would you have?”

“Well, it is nice to know you are not so arrogant,” she said.

The ice broken, we chatted until finished eating. Her amigas took turns strolling by on the walkway outside, smiling, waving, or winking to her as they passed, but hardly acknowledging me. They eventually crammed back in the Oldsmobile without her and rolled out onto the Strip.

After I paid for our food and drinks, we walked together out to the Stude. We didn’t hold hands and she didn’t take my arm. She seemed comfortable with me by then, but I didn’t think she’d appreciate me trying to move that fast.

I opened the passenger door for her and she climbed in. I went around, slid behind the wheel, and started the engine.

“This is the loudest car in California,” she remarked. “I always hear when you are in town—even miles and miles away.”

“Part of being the fastest is the noise.”

She nodded and pursed her lovely lips. “You are maybe a little arrogant, I think.”

We made a couple circuits of the Strip, then I stopped for gas.

“How you doing?” I asked Fatyma. “Anything you’d like to do?”

“Like what, Ike?”

I shrugged. “Bowling alley’s open. Golden Gate Golf. Or I could take you home if you’re bored or turning into a pumpkin.”

“Why do boys say that?” she asked. “Cinderella no turns into a pumpkin—her carriage does. And I am not bored. I have fun.”

“Okay,” I said. “You wanna cruise the Strip some more?”

She shrugged. “Is there somewhere else you want to go?”

“We could always go to the submarine races.” I watched her for a reaction.

“If you want,” she said, fluttering her eyelids.

I left the Strip and set a course for the river.

Fatyma was pleasant company. I liked that she would wave to friends in other cars, but didn’t try to make a big production of it to catch everybody’s attention…like cheerleaders and others would do. It was a shame I hadn’t been able to date her in school.

The traffic thickened as we got close to the Point. When we reached the river bank there were at least a dozen cars parked already. I prowled around looking for a spot, with my headlights off. It wasn’t cool to sweep your lights over other cars, or park too close to somebody else.

Again, I considered the historical/generational lottery. Nobody there and then needed to worry about finding a job, but 20 years before, that was a big concern. Nobody had come to the Point because they were shipping out tomorrow for overseas and this might be the last time their sweetheart ever saw them again—though plenty of that had happened 15-18 years ago. Nope—they were parking here simply because they could and they wanted to.

I didn’t want to be a weak man, but I sure loved living in easy times.

“Why do you call this ‘submarine races’?” Fatyma wondered. “Because submarines come down the river at night? You buy tickets?”

Was she really so innocent? “I dunno.”

“Oh, you know very well what happens here, I think, Isaac Jaeger.”

“I know people who come watch them seem to really enjoy it.”

I pulled into an empty spot, engaged the emergency brake and killed the engine with the transmission still in gear. Without the rumble of my engine, the night fell quiet. I turned the radio back on, softly, hoping Ross the Boss would help me out by setting the right mood. A commercial ended and he spun “Stay” by Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs. That wasn’t too far off the mark.

“So you want to ‘really enjoy’ this night with me, Ike?”

“Don’t you want to enjoy this night?”

“Maybe if the submarines have a very close, exciting race. Should we walk down to the water for a good look, maybe?”

“Knock it off,” I said. “What do you call it, anyway?”

She giggled, then said, “I always hear it called ‘Lovers’ Lane’.”

“You’re not so innocent,” I said.

“I am not?” Fatyma was a goddess in broad daylight, but the moonlight really enhanced her beauty. She didn’t have to try to look cute, but when she did, it was overwhelming.

The Zodiacs’ lyrics couldn’t have been timed better:

Won’t ya place your sweet lips to mi-i-i-ah-ah-ah-i-ine?

Won’t ya say you love me…all of the ti-ah-ah-ah-i-ime?

Stay!

Whoa-wo-wo-yeah just a little bit longer…

Please!

Please, please, please please, tell-a-me you’re goin’ to!

I scooted out from under the wheel, close to her. She scooted along the bench seat toward me.

“Isaac?” She bit her luscious lower lip and appeared almost bashful for a moment.

“What’s on your mind?”

“I have something to tell you.”

“Tell me.”

Her eyelids drooped as her mouth drew so close to mine that I felt the heat of her breath. “I would have dumped Luis for you, I think.”

Ross the Boss provided the mood music while I got caught up in a starburst of passion.

Easy times, indeed. Life was so good, it felt as if the easy times would never end.