I took my football everywhere I went. When there were no other boys at the trailer park who wanted to toss it or play a game, I would play with Ace down at the grassy park. She didn’t exactly understand the rules of football, but she could bite down on the pointy end of the ball and run from me. She could also chase and tackle me when I had the ball.

On one of those excursions with Ace, after we played for about an hour, I walked over to the outdoor water fountain for a drink. While leaning over and sucking in the cool water, the football was slapped out of my hand.

I straightened and turned, wiping my mouth. Two black kids stood facing me with belligerent expressions. One of them held my ball.

If I had taken to heart what Uncle Si had told me about always being aware of my surroundings, that wouldn’t have happened.

I approached the kid holding my ball with hands extended for him to give it back. Before I reached him, he threw it to the other kid. This quickly developed into a game of Keep-Away, and I was “it.”

Every time I went after my ball, one would hold it out to tease me before tossing it to his accomplice, smirking. My retarded dog just sat there watching all this, curiously. She had seemed a lot happier to see me each day since I had started running with her in the evenings, but evidently that wasn’t enough for her to stick up for me this time.

I didn’t recognize the boys—maybe because they were in a higher grade; or maybe because they went to a different school.

“You want the ball, white boy?” The taller, skinny one taunted, holding it out. “Here ya go.”

I reached for it.

“Uh oh, too slow,” he said, tossing it to the stocky boy who was only an inch or two taller than me.

“Wha’sa’ matter, Saltine?” the other one jeered. “Why don’tcha’ just get yo mama to buy you another one?”

Realizing I was not gonna get my ball back this way, I stopped chasing it. “Go get your own ball,” I said, voice squeaking. “Give mine back.”

The skinny one’s smirk disappeared and his nostrils flared in rage as he took quick steps toward me. “What you say, mothafucka? I know you ain’t talkin’ to me!”

He got up right in my face, moving his head around as he talked, as if trying to smell different parts of me. I instinctively took a step back to get breathing room, but he stepped forward to close the gap again. It was like he fed on my fear, or something. The more intimidated I was, the bolder he got.

“This is our park, mothafucka,” he told me, then pointed across the railroad tracks to where the shabby trailer lots were. “Yo punk cracka’ ass betta’ run the hell up outa’ here befo’ I kick yo ass right now.”

“I’m not going anywhere until you give it back,” I said, with a quavering voice that sounded pathetic, even to me. “It ain’t your ball and this ain’t your park.”

“What! What the fuck you just say to me?” His spittle splattered my face as he yelled.

I had heard a conversation between Uncle Si and one of the men who trained at The Warrior’s Lair. Uncle Si started out by telling the man that weapons or martial art skills weren’t the most important factor in a fight—the most important factor was your willingness to use them. He went on to say that there comes a point in any confrontation when you know that violence is inevitable. Rather than go through all the insults, pushing and shoving, you might as well just get it over with—and none of that noble nonsense about waiting for the other guy to throw the first punch. If you caught the other guy unprepared, that was his fault.

I flicked out a left jab while slipping my right foot back and assuming the stance I’d been practicing so much for months. It caught him right on the mouth and split his lip, shocking him. But Uncle Si had taught me to always punch in combinations, so before the boy had time for it to register that I hit him, my straight right mashed in his nose. He blinked involuntarily while I nailed him with a double hook that rocked his head back. To my amazement and delight, the skinny kid went down with blood gushing from his nose.

The other boy was in the process of charging me from behind. He had probably sprang into motion when his buddy suffered that first blow, and now he was almost on top of me. I shuffled laterally, pivoted, and fired a third hook down low, catching him hard in the stomach. He grunted and froze in his tracks, his complexion going pale as he wheezed and bent forward at the waist. I stuck my jab in his face once, twice, then unleashed an uppercut that caught him right on the jaw, just as I’d been taught at The Warrior’s Lair.

The stocky boy staggered forward as I sidestepped and landed another jab and a cross for good measure. He fell on his face.

The skinny boy was trying to get up.

I’d also heard Uncle Si talk about the fight scenes in old movies. The telegraphed roundhouse punches in those farfetched scenes were dumb. Even dumber was how the combatants stood still, waiting for a dramatic haymaker to hit them, before it was their turn to throw a counterpunch. But perhaps most idiotic of all: after knocking the villain down with one of those haymakers, the hero would waste energy pulling him up to his feet before hitting him again. It must have seemed gentlemanly or something to audiences a long time ago. But Uncle Si said only a fool would try something like that. He talked about what you should actually do, instead.

I pounced on the boy before he could get up, driving my knees into his armpits, and used his face for a heavy bag, unloading shot after shot with both hands, until his face was a bloody mess.

It’s hard to describe the satisfaction I felt every time my fists connected with his flesh. Feeling that blunt force shock travel from my knuckles up my arms was like a powerful drug. For the first time in my life, I was in control of my circumstances. Nobody could say or insinuate that I was inferior. Especially not that skinny asshole on his back, who I was pounding on.

I climbed off him and looked to see what the other kid was up to.

His mouth was bleeding, too. He had rolled onto his back and was using one leg to scoot himself backwards through the grass, away from me.

I picked up my ball from where it had fell, watching both kids to see what they would do next. Neither of them seemed interested in stealing my ball, anymore.

Then the fear returned. I had just assaulted black kids. I had learned about assault, and racism, from all my teachers ever since First Grade. I didn’t understand why, but if a white person did something to a minority that minorities liked to do to white people, it was wrong and you were in deep, deep trouble.

Of course on TV and in the movies, blacks were always the victims of harassment and assault from white people. Every single time—no exceptions. That was also how politicians and the media looked at race relations, too, even decades after the Civil Rights movement had torn down the Jim Crow laws and made discrimination against minorities almost universally reviled. Reality, however, did not conform to that authorized narrative.

Football under one arm and retarded German Shepherd trotting along behind me, I ran back to Mom’s trailer.

It was hard to sleep that night, so scared that any minute the cops would arrive to arrest me for a hate crime.

By morning they still hadn’t come.

The only person I thought I could trust was Uncle Si. When I saw him the next day, I told him what happened.

For a while, as I described the fight, he looked confused. When I finished, he was quiet and thoughtful for a bit before suddenly nodding his head as if he’d just decided something.

“How are your hands?” he asked.

“Sore,” I said, a little surprised by the question.

He produced ice packs from the freezer in his office fridge and affixed them to my knuckles with training hand wraps.

“We’ll make it a short day,” he said. “No bags. Just rope, footwork, and shadow boxing. We’ll see how your hands feel tomorrow—might need to rest them for a few days.”

“They didn’t hurt at all at the time,” I said.

“Your adrenaline numbed the pain. But a bare-knuckle fight takes its toll on both sides. In a street fight you’re probably not gonna have time to slip on gloves, Sprout. So remember: soft-to-hard; hard-to-soft.”

“I don’t think you taught me that,” I said.

“The second kid,” he said, “you got him in the stomach. The stomach is soft; the fist is hard—you can use your fist on that target. Hard-to-soft. That’s not what bruised your knuckles. If you’re gonna hit somebody on the jaw without gloves, use the heel of your hand, or your palm. Soft-to-hard. Lucky you got strong bones—some people might have broken their hands.”

He raised both his fists so that the backs of them were to me. “See that?”

I looked closer. One knuckle on his right hand sank in considerably farther than the corresponding knuckle on his left.

“I broke that one, and it took several months to heal. Couldn’t do a damn thing with that hand.”

“Hard-to-soft; soft-to-hard,” I said. “I got it, Uncle Si. But what about…what if the cops come for me?”

He shook his head. “I don’t think those kids are gonna want to tell anybody what happened.” He sighed. “Of course, if they do, they’re gonna lie about it. They’ll say it was you and a bunch of other guys that jumped them, most likely. That you stole the ball from them, maybe. I still have the receipt, so we can set that part straight. They’ll want to bring race into it, somehow. Say that you and your redneck buddies called them the N-word. You attacked them because they’re black.”

“You think so?”

He shrugged. “Like I said: they might not say anything. But if they do, we’ll have to play it by ear. In the old days, we could just say it was self-defense, because it kind of was. Today…well, they’ll say you should have just given them the ball and walked away. That would teach them a more profound lesson than violence ever could. You’d be the more respectable person that way, blah blah blah.”

“But you gave me that ball,” I protested. “If I let them take it, it’d be gone for good.”

“I’m not saying that’s what I think you should have done,” he said. “And as far as the ball goes, don’t worry about it. If they had managed to steal it, I’d have gotten you a replacement. Okay? But something more important than a football was at stake.”

“Huh? What do you mean?”

Uncle Si tapped his index finger against his temple. “Now you know: you’re not a wimp; you’re not a coward; you’re not inferior to other people at all.”

I didn’t know how to accept compliments. Especially from a grownup. “I’m sorry, Uncle Si. I heard you talking to one of your students. About willingness to fight, I mean. I wasn’t trying to eavesdrop.”

He watched me closely for a moment before responding. The intensity of his hard eyes could be unnerving, when he had the sunglasses off. “Well, I hope he listened half as good as you did,” my uncle said, with what might have been a tight-lipped smile (it was hard to tell—he was usually so unexpressive). “Don’t apologize. What you did was learn from someone else’s mistakes. That was smart. Not everybody can do that. I had to learn those truths the hard way. So you’re already adopting The Way of the Warrior, and I haven’t really even started teaching you the mental component, yet.”

I wasn’t intending to bring up the guilt I felt for enjoying the euphoric rush while I smashed the one kid’s face in. But like so many other times with Uncle Si, it was like he already knew, anyway.

“There’s a couple pitfalls you have to avoid,” he told me. “First, don’t get addicted to the power you felt. Okay? Don’t go looking for fights so you can feel it again. If you have to fight, then fight like hell. But if you don’t have to, then don’t. You’ll be a better man if you try to be peaceable.”

I nodded. “What’s the other thing?”

“It’s gonna sound like the same thing I just told you, but it’s not. And that is: don’t get cocky because you know you can win a fight. Overconfidence leads to arrogance; arrogance leads to carelessness; and carelessness leads to defeat.”

I nodded again. I didn’t like arrogant people and never wanted to be one.

“It’s fortunate those two didn’t know how to fight as a team,” he went on. “I haven’t taught you anything about dealing with more than one attacker. And you haven’t learned any grappling yet.” He turned thoughtful again, staring into space. “I wouldn’t mind taking a look at that fight…”

I squinted at him, tempted to tell him that was impossible, now that the fight was already over.

“…But it sounds like you did okay,” he concluded. “Go get dressed and get started on your footwork.”

The Warrior’s Lair had a shower in the locker room. He had me use it before leaving that day. Then, instead of driving me home, he took me to a go-kart track. I spent hours racing and playing video games in the arcade. He seemed to derive some sort of enjoyment by letting me play around, so I didn’t feel as guilty about him spending the money as I normally would have. He even played some video games himself.

The summer was off to a great start.

UPDATE: This book is published! Click here to buy on Amazon.

Click here to buy anywhere else.

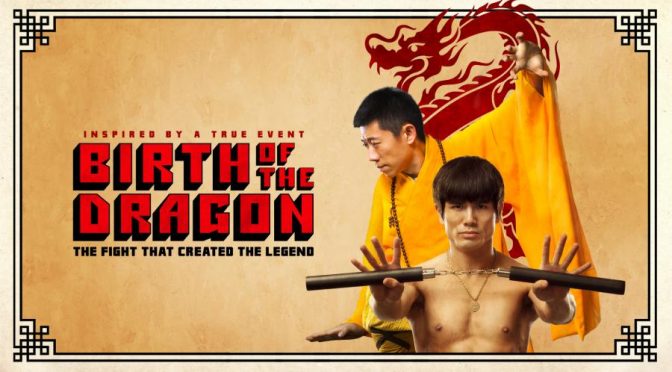

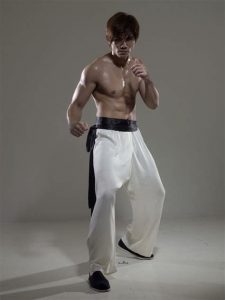

The acting is good–especially Xu Xia as Wong Jack Man. Philip Wan-Lung Ng has a physique much like Bruce Lee, and has mastered Lee’s poses, gestures, and movement. This was displayed best when fighting or sparring, when he would dance around his opponent (in western boxing this is called “the bicycle”–Bruce Lee’s bicycle was distinct and rather flamboyant).

The acting is good–especially Xu Xia as Wong Jack Man. Philip Wan-Lung Ng has a physique much like Bruce Lee, and has mastered Lee’s poses, gestures, and movement. This was displayed best when fighting or sparring, when he would dance around his opponent (in western boxing this is called “the bicycle”–Bruce Lee’s bicycle was distinct and rather flamboyant).